Last updated on September 11th, 2021 at 02:46 pm

In between her shifts, Zimbabwean nurse Sinothando Mpofu used to go to Bulawayo’s open-air markets to buy tomatoes and cabbages for her family of nine – until the country’s coronavirus lockdown closed all stalls.

Ms Mpofu worried about where she would get fresh food, until she saw a message in her local church WhatsApp group about Fresh in a Box – one of rising numbers of African tech companies getting fresh food to people under lockdown.

Now she puts in an order online and gets a box of produce delivered to her home every week. The fruits and vegetables are better quality than the food she used to buy at the supermarket, she said, at about a third of the cost.

“Buying vegetables at a local supermarket is very expensive, but now I get a variety of vegetables and I eat balanced meals all the time,” Ms Mpofu, 37, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation, saying she will keep using the site even after lockdown ends.

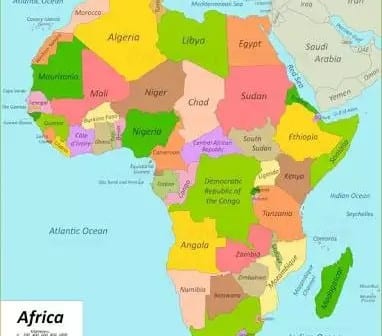

In many African countries, measures put in place to slow the spread of Covid-19 have made it harder for people to access affordable, nutritious foods, sparking warnings from aid groups that the pandemic will worsen malnutrition rates.

An estimated 73 million people in Africa are already acutely food insecure, noted Matshidiso Moeti, the World Health Organisation’s Regional Director for Africa in a press release last month.

“Covid-19 is exacerbating food shortages, as food imports, transportation and agricultural production have all been hampered by a combination of lockdowns, travel restrictions and physical distancing measures,” she said.

A possible global GDP loss of 5 per cent this year could push another 147 million people into extreme poverty – more than half of them in sub-Saharan Africa, according to the DC-based International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

The app, which started in South Africa nearly one year ago, acts like a version of food remittances, allowing people in South Africa to order groceries for delivery in Zimbabwe.

While 70 per cent of products are sourced locally in Zimbabwe at cheaper rates, about 30 per centb come from South Africa where Malaicha has permission to import goods.

Nokusa Nyathi, 24, stood in a snaking queue of up to 200 people at the Malaicha pick-up point in Bulawayo, waiting to get the parcel of goods that her father in South Africa had ordered online – essentials like cooking oil, sugar, spaghetti and soap.

Through Malaicha, her father can get groceries to his family in a few days, compared with the weeks or months it can take to send the food from South Africa to Zimbabwe, Nyathi said.

Using the service is also cheaper than if her father simply sent money for his family to buy the food themselves, she explained.

“Coronavirus pushed us in the right direction,” said De Beer, who believes the app’s steep surge in users will last long after the pandemic.

The company is so confident about the future of online food shopping in Africa that it is launching Malaicha Global next week, said De Beer, so that people can send goods to Zimbabwe from anywhere in the world.

“The need is simply too big to die down,” she said.

(Thenational)