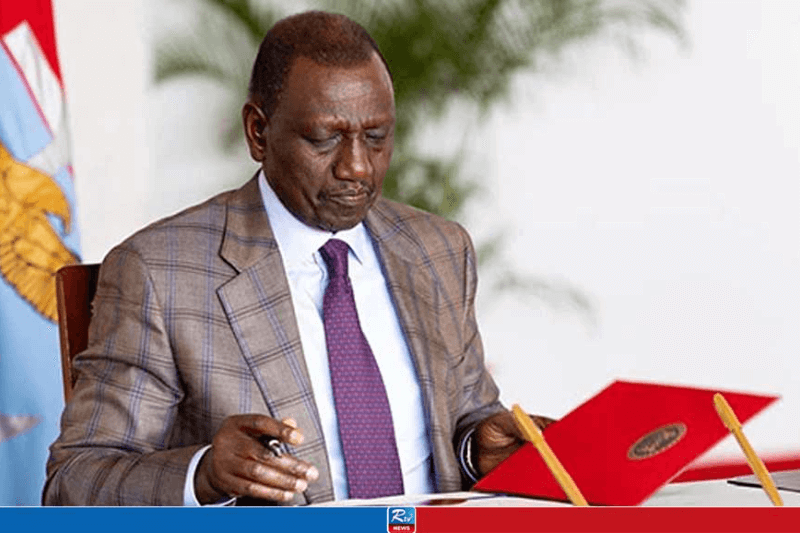

Kenya, the economic hub of East Africa, is expected to incur even more debt following the rejection of a finance package that President William Ruto had insisted was essential for generating revenue, due to violent demonstrations. .His most recent forecast is, “It will have huge consequences.”

In response to numerous demands that he resign, Ruto has stated, without specifying where the money will come from, that the government will borrow the remaining $2.7 billion to reduce the budget deficit by half.

Ruto has also promised funding cuts in his own office and said funding would stop for the offices of the first lady, the “second lady,” the wife of the vice president, and the wife of the prime Cabinet secretary after anger over bloated bureaucracy and luxurious lives of top officials helped to fuel the demonstrations. There will be closing of around four dozen state companies with overlapping responsibilities.

Over his attempt to pay taxes needed to help Kenya pay back its $80 billion public debt to lenders, including the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and China, Ruto has grown more unpopular in his two years of power. At almost 70% of Kenya’s GDP, the national debt is the highest it has been in twenty years.

The crucial question is how Ruto’s government will find the money to pay off debt without aggravating millions of Kenyans barely making ends meet and without depressing the economy. In 2023 the GDP rose 5.6%.

Former adviser to former President Uhuru Kenyatta, economist Mbui Wagacha, said Kenya needs a professional budget and management authority like to the Office of Management and Budget in the United Kingdom. The treasury of Kenya now generates budget projections and transmits them to the legislative finance committee, which generates the finance bills.

Wagacha remarked in an interview, “Parliament looks after its own interests; it has abdicated its mandate on the public finances in the Constitution.” He warned additional borrowing by Kenya might be “disastrous” and suggested a diplomatic approach to draw investment and debt restructuring to try to get creditors to write off part of it.

Economist Ken Gichinga agrees that Kenya’s borrowing will slow down the economy. Despite efforts to recover from the COVID pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine, he noted that many companies are still struggling.

Government borrowing causes interest rates to rise. Companies cut back on spending and the economy experiences a slowdown when interest rates increase, according to Gichinga.

The president of Kenya has promoted self-sustainability, arguing that instead of borrowing, the nation should increase income. “We have to be able to improve our taxes if we are a serious state,” he declared in May. Kenyans, meanwhile, have turned down plans to increase taxes as they battle growing prices on basic commodities; they have even stormed parliament during recent demonstrations.

Keep Reading

Days after declaring he would not be signing the finance measure he had supported, Ruto claimed last week he had worked hard “to pull Kenya out of a debt trap” and that major repercussions lay ahead.

Wagacha argued that government increases in revenue targets and tax collecting come second in terms of economic growth. People have money in their pockets and you build an enlarged economy with jobs and investment. They will find it much simpler to hear about your tax request.

Saying small businesses hold the key to Kenya’s economic development since they typically absorb many people, he recommended making access to low-interest finance simpler for companies in important industries like tourism and agriculture. That might assist to reduce young unemployment rates.

“At the end of the day, we need a jobs-centered economic policy,” Gichinga said, urging the government to reward companies to generate employment via low taxes and reduced interest rates. We have so been lacking it.

Public discontent in Kenya has focused on the IMF, which proposed some of the divisive tax measures. Some demonstrators carried posters bearing statements like “IMF stop colonialism.”

Late last month, the IMF said in a statement that it was keeping an eye on Kenya’s condition and that its main objective was to enable it “overcome the difficult economic challenges it faces and improve its economic prospects and the well-being of its people.”

Beyond only stressing debt sustainability, Gichinga said the IMF should be a “strong development partner” for Kenya.